What is the human body? How do we experience it, reflect on it, contemplate it? These are the questions that La Veronal explores in their performance Siena. But don’t expect to leave the theater with clearcut answers. La Veronal is in the business of suggesting the mystery, rather than solving it.

Marcos Morau (1982) seems thrown off by the question. For the past hour, the young choreographer and director of La Veronal has talked passionately about the ideas he tries to communicate on stage in the dance performance Siena, an exploration of our perception of the human body throughout the past five centuries. “When is a performance successful?”, I ask him.

Marcos looks startled, almost offended. “I hope to cross the border, to have a dialog with the audience. But how do I know if this has happened? I have to ask every single member of the audience.” For a moment, he looks lost. Tries to find the proper words. Then sighs. “It is a feeling. How do you describe that feeling? That’s the whole point of the piece.”

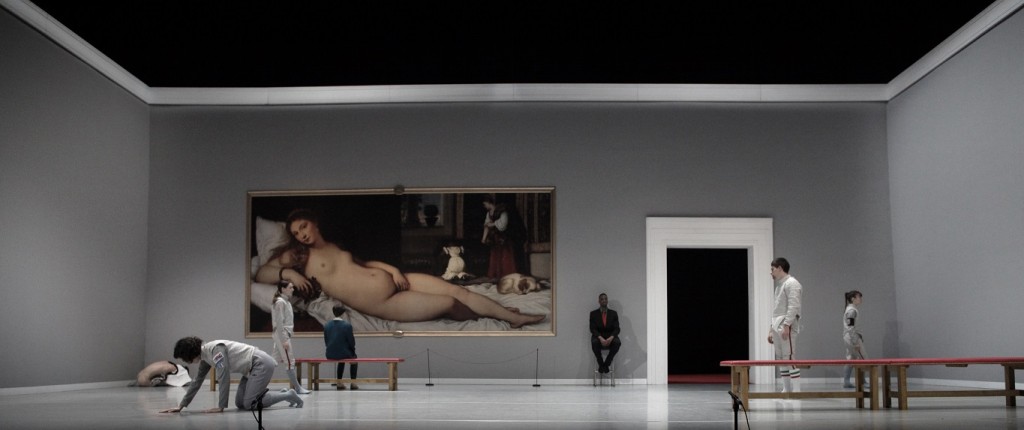

That struggle for words is not unlike what I experience some hours later, after the curtain has fallen on Siena. For an hour, La Veronal has swept me up in their dazzling, multi-sensory world of dance, music and literature. One moment, you are watching a woman observing a painting in a deserted museum. The next moment, that same museum is filled with dancers dressed as fencers, who entangle and disentangle in furious, fluid movements. A voice blasts through the speakers, narrating the story of a deadly accident, inter merged with laughing tracks. It feels as if it is all connected, in a surrealistic, slightly disturbing way. But is it?

This is the world La Veronal likes to suck her audience into, and with which the young company from Barcelona has quickly made a name for itself in the world of contemporary dance. It is a world that feels familiar, but isn’t quite like the real world . A subconscious, associative world, that draws just as much on the icons of dance history as on the surrealistic storytelling of David Lynch and the imagery of Pasolini.

Marcos Morau, who with his horn-rimmed glasses, ruffled short hair and two week stubble appears more like an indie-filmmaker than one of the hottest young choreographers in contemporary dance, founded La Veronal in 2005 together with kindred spirits from the world of dance, film, photography, music and literature. The artistic collective is constantly exploring new ways of telling stories, creating a strong expressive narrative by drawing on a diverse set of cultural references across different artistic disciplines. This comes to the fore most clearly in the series Decalogue, a collection of ten shows of which the starting point is a city or a country in the world. From that point, Morau establishes a connection between geography and dance.

In Siena, that geographical starting point is the historical city in Tuscany, closely associated with the birth of the Renaissance. In the Middle Ages a thriving hub, Siena lost its battle for economic and artistic supremacy in the Renaissance from Florence. Like the other settings in the Decalogue, however, the piece Siena hardly resembles the actual ancient city. The Siena of Morau is a faintly familiar landscape. A canvas where the imagination arrives and bleeds into realism. In this recreated Siena, memory and fantasy merge. Music and dance, setting and imagery are out of sync, sometimes even distorted. Yet in a strange way, they also feel like they are telling one story. One argument. One idea. One philosophical exploration.

The subject that is explored in Siena is the human body, and how artistic and societal perspectives on the human body have changed throughout the centuries, Morau explains to me. “Before the Renaissance, God was the center of artistic and intellectual world. But with the birth of humanism, our focus shifted from God to the human body, to the individual person. The question I am putting on stage before the audience is: where is the body now? What kind of humanism do we have now?”

They seem big questions to capture in a single, one-hour long dance performance. And certainly, Siena muses on a lot of different human bodies in a multitude of contexts. The observed and contemplating body in a museum. The fighting body in a fencing match. The departing body in a funeral home. The chilling potential of the mass body, evoked by speeches of Mussolini and Berlusconi. The naked body, uninhibited and voluptuous, as it looks us straight in the eyes from the huge canvas on stage. Through narration, unseen bodies are introduced into our minds.

These are the rough brush strokes. Tangible, recognizable contours of a familiar situations. A gateway, as it were, between the real world and the world created on stage. Center of that world on stage is the dance. The erratic, fluid dance-vocabulary in which the dancers move in and out of the frame. At times rapid, furious, and out of sync, then again abstract and disconnected, or soothingly lyrical and in harmony, the movement of the dancers on their own are void of meaning.

But when they are interwoven with the setting of a scene, the baroque music, the narrated text, Moraus highly technical and visually choreography is the rhythm that ties Siena together. Just like the physical body itself, it becomes a vessel for emotions, a container of feelings. A visual language, that does not express the story of the body, or represents anything into a singular narrative, but weaves together a multitude of possible stories.

What these stories are, however, are left to us spectators to piece together. For Morau that is kind of the point of his shows. “I don’t try to give the audience answers,”he says. “The audience has to connect the context, the music, the words, the movement of the dancers. I believe that in contemporary dance, you don’t have to tell the audience something. You have to suggest..”

What he strives for, he tells me, is creating a ’third picture.’ That ’third picture’ is what happens when what the performers do and stage and the way the audience receive the movements, visual, sounds and text presented to them transform into a new picture. A picture that only exists in the brain of the spectator.

Next to the exploration of the body, then, there runs a second theme through Siena. It is the thread that connects all of the La Veronals work together. That second theme is the exploration of art. What defines art? What should it do? For Morau, art is much more than a play with visuals, than a choreographed sequence. “It is a multi-sensory experience. Of course it is dance, it is beautiful. But for me the point of art always is to represent the world you are living in. It’s not science, it’s not sociology, but it’s how you understand your world. ”

He pauses for a moment. “For me, a piece is dialog. My responsibility is to share my world, but the audience needs to know that the piece is not a present. It is a donation, but it comes with a responsibility. I give you my world, but you need to do something with it.”

As I leave the theater, I wonder what I will do with the show. What my third picture is. If I actually created one. The performance is still resonating within my body. Within my ears, my eyes, it crawled under my skin. I feel like I have been carried off into some rapturous, ecstatic poem, that feels strangely close to my world. But when I try to put that sensation into thoughts, I am lost for words.